Koldo Basterretxea, Associate Professor at the University of the Basque Country/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI), which provides accurate information on the reflectance spectrum of materials, is already being used successfully in various fields of application such as Earth observation, geosciences, precision agriculture, space exploration and the food industry [1]. In recent years, advances in HSI detection technologies have enabled the commercialisation of snapshot cameras capable of capturing spectral information in tens or even hundreds of bands at video speeds [2]. These developments have sparked great interest in exploring the potential of HSI in emerging fields of application that require affordable, compact, and portable spectral imaging systems with moderate to low power consumption. The Digital Electronics Design Group (GDED) at the University of the Basque Country (EHU) began exploring the use of HSI sensors in the development of future vision systems for autonomous driving (AD) several years ago. The objective of this line of research is to analyse the potential of HSI to overcome the robustness limitations present in current intelligent vision systems, as well as to investigate the possibilities of expanding the capabilities of these systems in order to provide greater scene understanding [3].

The integration of HSI snapshot cameras into AD requires careful analysis of the available technologies, as well as the adaptation of both the algorithms and the processing architectures of the vision systems to the particular requirements of this field of application. The challenges in this field of application arise from a combination of several factors that affect the quality and accuracy of the information collected by these sensors: the limitations inherent in the different snapshot camera technologies, the lack of control over the lighting of objects, the presence of fast-moving elements, variable exposure times, etc. Thus, the selection of an HSI camera for experimenting with the development of advanced computer vision systems applied to AD must be based on a set of well-established criteria. Ideally:

- It must be capable of operating at video speeds (snapshot cameras) under different lighting conditions.

- It must be small, compact and mechanically robust.

- It must offer sufficient spatial and spectral resolution to achieve good spectral separability between the classes or materials to be identified.

- It must be based on scalable sensor technology that makes it competitive for future mass deployment.

When it comes to the ability to operate at video speeds, an additional factor that is often overlooked but is of extraordinary importance is the processing requirements necessary to recover spatial and spectral information from the raw data provided by the sensor. The main players in the small-format, high-speed (> 10–20 fps) HSI snapshot camera segment employ either on-chip deposition technology for narrow-band interferometry filters (e.g., Imec sensors used in Ximea and Photonfocus cameras), or light field technology based on microlens arrays for multiple projection of spectrally filtered images onto the sensor (as in the case of Cubert). In both cases, the incident light is projected onto a standard CMOS sensor, which currently provides an advantage in terms of the availability and scalability of these technologies. Alternative technologies, such as Coded Aperture Snapshot Spectral Imaging (CASSI), combined with scattered spectral sampling, require complex and computationally intensive data processing, which means that these cameras are currently unable to meet the aforementioned requirements for use in autonomous driving applications. There are some new emerging technologies, such as the one developed by the Finnish company AGATE, which, although promising, has not yet been evaluated.

The HSI-Drive dataset

Research in this field requires, first and foremost, one or more datasets that did not yet exist when the GDED began this investigation. The HSI-Drive dataset was obtained from field recordings made with a Photonfocus MV1D2048x1088-HS02-96-G2 camera equipped with a 25-band Imec sensor in the Red-NIR range based on on-chip mosaic filter technology (Fig. 1).

The main reasons for choosing this technology were its relatively low cost, high speed combined with acceptable spatial and spectral resolutions, and the accessibility of a spectral cube generation processing code that was not overly complex, thus facilitating its adaptation and reprogramming for efficient execution on an embedded processing platform. In addition, spectral filter-on-chip technology offers much greater scalability than its competitors, so the fact that these sensors could be mass-produced at a cost similar to that of traditional CMOS sensors was particularly appreciated.

However, there are also some drawbacks to this technology that must be considered, such as spectral leakage and second-order response peaks, the limitations imposed by mosaic patterns on the number of bands, and the need for spatial realignment of pixels according to these mosaic filter patterns. Overall, our approach to the development of HSI-Drive was fundamentally based on the principles of simplicity and feasibility, with an engineering focus in which the future realisability of the developed systems has been a cross-cutting factor throughout the research. This dataset, which contains 752 manually labelled images at the pixel level and is publicly available to the entire scientific community, is now available in version 2.1.1 [4].

The data processing pipeline used to generate hyperspectral cubes in HSI-Drive 2.1 has been optimised to simplify its execution as much as possible, as this process can generate the main bottleneck of the application in terms of computational load. In summary, the process consists of the following phases:

- Image cropping and framing.

- Bias removal and reflectance correction.

- Partial demosaicing (with a spatial resolution loss of 1/5).

- Spatial filtering (optional).

- Centre translation (band alignment using bilinear interpolation).

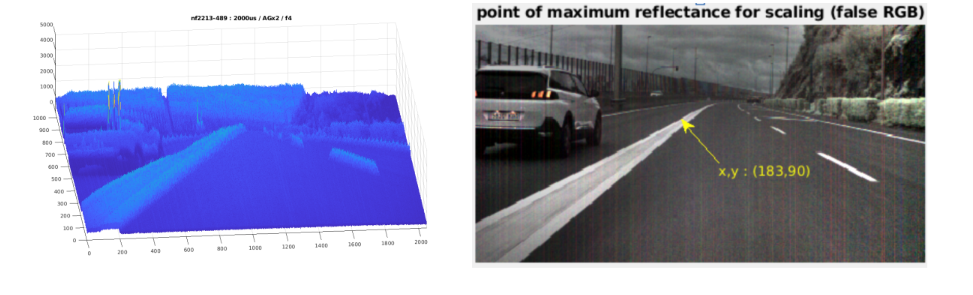

Reflectance correction is a particularly sensitive process, as its aim is to cancel out the illuminant’s irradiance spectrum and isolate the reflectance spectrum from it. In a laboratory setting, this can be done using a calibrated white tile and correcting the image data to be processed with data from a white reference image acquired under the same lighting conditions and with the same camera settings. Under dynamic field conditions, however, accurate reflectance correction is not possible. At GDED, we have developed a reflectance ‘pseudo-correction’ algorithm that improves data consistency by using data from the image itself to estimate the relative illumination levels of each scene. This estimation is performed dynamically or ‘on-the-fly’ by identifying the pixels with the highest albedo in each image, which usually correspond to high-reflectance white surfaces, typically road markings on asphalt or other reflective white paint, white-painted vehicle bodies, etc. By comparing the irradiance of these pixels with calibrated white reference images, a scale factor is calculated that allows for correction. Identifying reference pixels for scaling is not trivial, as it involves discarding pixels from artificial light sources (light emitters), such as traffic lights, traffic signals, or vehicle headlights and taillights. The implemented algorithm automatically segregates these ‘suspicious’ pixels based on their spectral signatures, requiring no human intervention and allowing this function to be integrated directly into the image processing pipeline of the segmentation processor (see example in Fig. 2). This new technique replaces the pixel normalisation (PN) used in previous versions of the HSI-Drive processing pipeline.

AI models for HSI-Drive

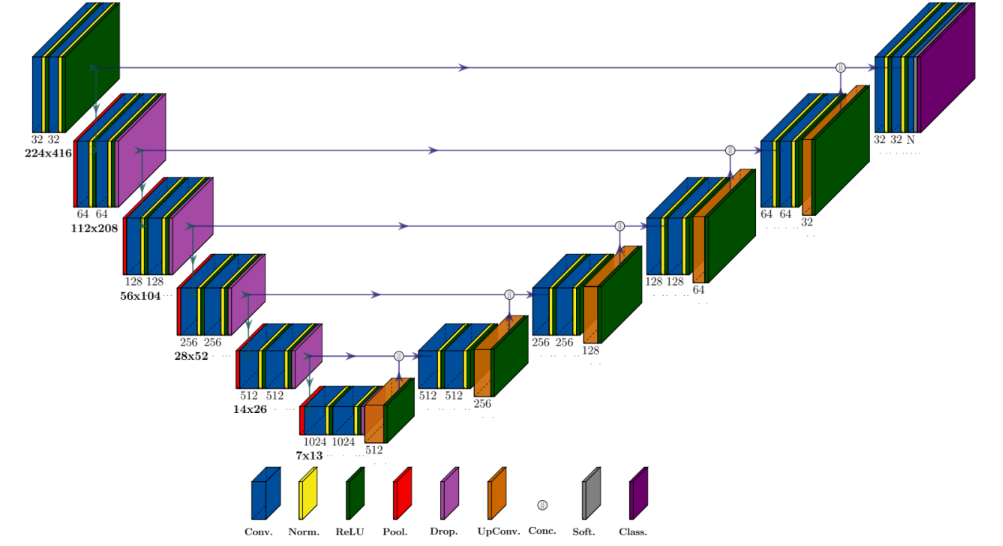

The HSI-Drive segmentation models are CNN (convolutional neural networks) encoder-decoder types with a U-Net structure (Fig. 3).

These models have been improved in the latest version of HSI-Drive through the incorporation of spectral attention modules. The attention mechanisms are inspired by the human visual system, where the brain selectively prioritises certain regions of the visual field while suppressing less relevant information. A similar principle is implemented in artificial neural networks by weighting feature maps using an attention function that allows the network to emphasise the most discriminative spatial and spectral features (or a combination of both), ultimately improving its representation capacity. In particular, the so-called Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) works by adaptively readjusting the features per channel without resorting to dimensionality reduction, and does so by applying a local interaction between channels using a fast 1D convolution with a kernel size determined adaptively based on the channel dimension. This design avoids the creation of additional neural layers and thus maintains both the accuracy and efficiency and simplicity of the base models, a necessary feature to keep model complexity under control and enable real-time execution.

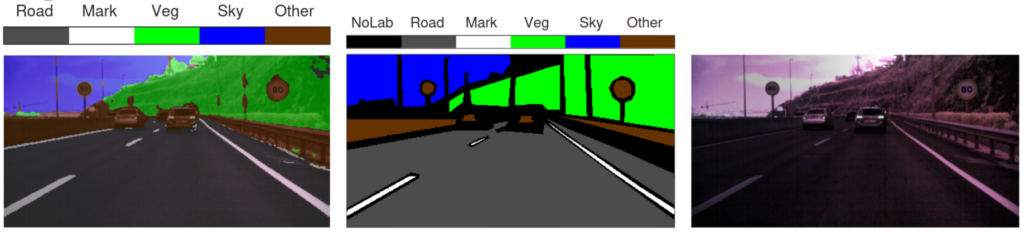

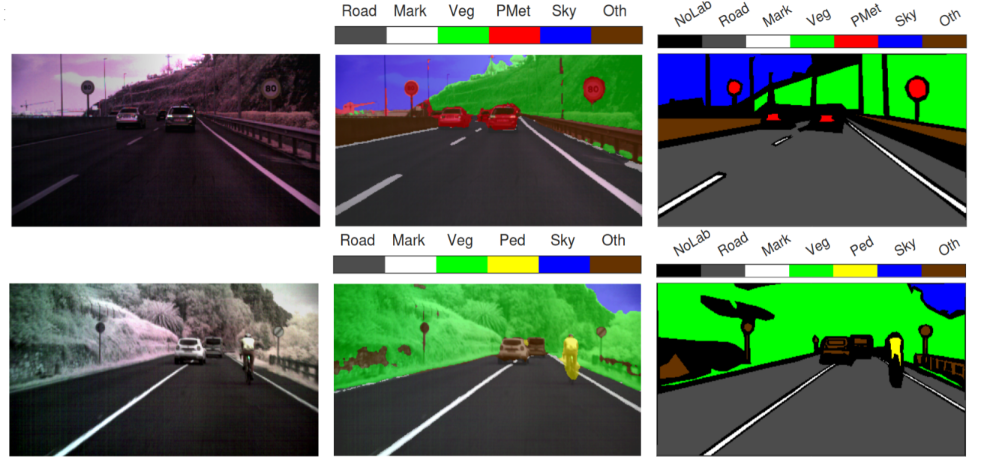

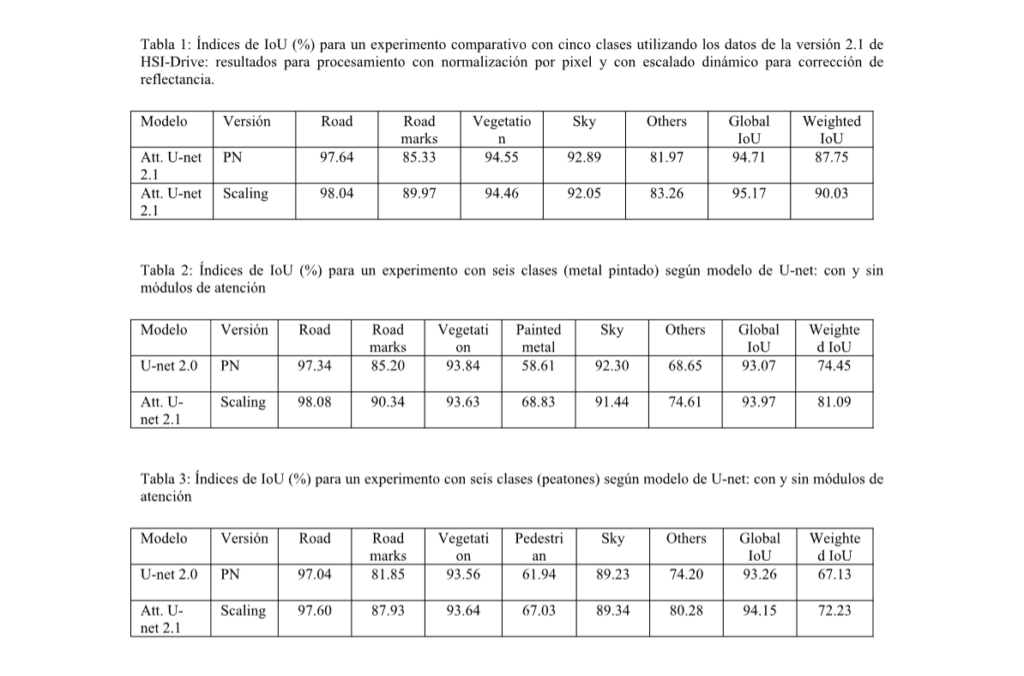

The results obtained with the new attention models on the HSI-Drive 2.1 data support both the incorporation of these new modules and the use of the pseudocorrection reflectance algorithm described above (dynamic scaling). With the incorporation of the attention modules, improvements in the most demanding classification indices (weighted IoU) of between 2% and 7% have been obtained, depending on the experiments and the number of classes to be identified. For their part, the segmentations obtained with the new dynamic scaling correction algorithm generate improvements of around 2% consistently in all the experiments carried out, with particular benefits in the classification of the most delicate classes due to their greater intraclass variability and lower interclass separability. Tables 1 to 3 show comparative test results according to the version of the database used (v2.0 or v2.1), the method applied in the treatment of reflectance values (PN or dynamic scaling), and the trained model (U-net or U-net with attention modules), both for an experiment with five classes (see segmentation example in Fig. 4) and in two experiments with six classes (see examples in Fig. 5).

The models were trained and tested using a stratified cross-validation strategy with three training sets, one validation set and one test set. The results in the tables show the average values after five training rounds. On the HSI-Drive website (https://ipaccess.ehu.eus/HSI-Drive/), you can see some hyperspectral video segmentation sequences performed with the best-performing models.

The HSI-Drive processor

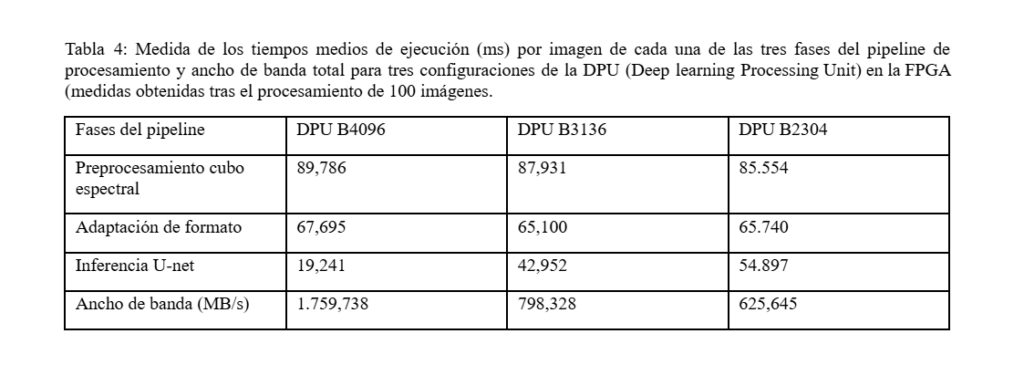

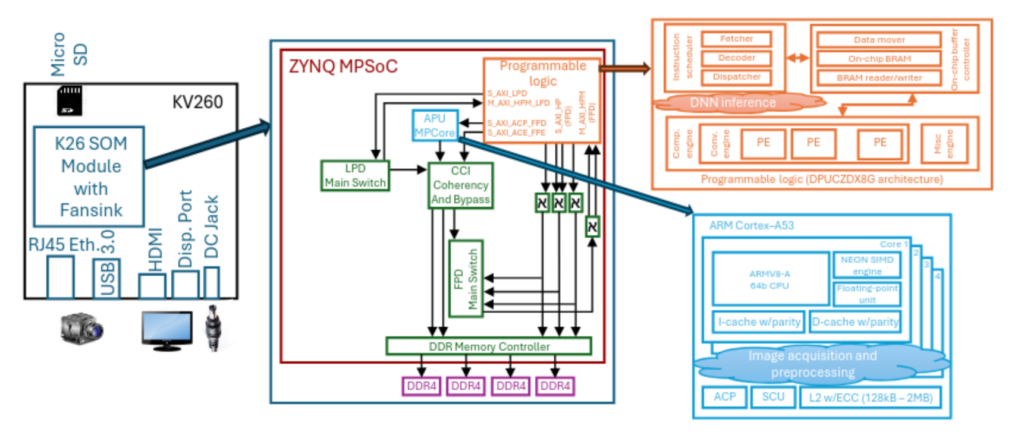

We have developed several prototypes with PSoC/FPGA technology for real-time processing of the HSI segmentation system, both for the pre-processing stage of sensor data (generation of hyperspectral cubes) and for CNN models for inference. One of the latest prototypes has been implemented on a low-power, low-cost AMD Kria KV26 SOM, suitable for embedding in mobile platforms. The processor performance characterisation values on this platform are shown in Table 4.

To achieve this performance, several advanced design techniques have been applied, both in terms of optimised model compression (quantisation, pruning, etc.) and SoC architecture and process synchronisation. In particular, a three-segment pipeline execution was designed for this implementation. The first two phases correspond to the pre-processing of the hyperspectral cube and the adaptation of the data encoding format for the subsequent inference phase, which are executed on two Cortex-A53 cores embedded in the K26 MPSoC, sharing the SIMD registers. In this version, the inference of the CNN segmentation model, which is controlled by a third software thread, is executed on a DPU B3136 IP core (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Schematic diagram of the HSI video processing system implemented on SOM KV26

This is not the highest possible performance version in the DPU configuration, and was selected to optimise consumption and resource usage in the FPGA. Synchronisation has been programmed using condition variables with independent output buffers to prevent races. This configuration achieves a maximum latency of 87.138 ms, i.e. a minimum video processing speed of 11.5 fps, which is slightly higher than the frequency at which the sequences for HSI-Drive were recorded. This performance is achieved with only 5.2 W of average power dissipated in the K26, so the energy consumed in processing each image, from the acquisition of the raw data to the segmented output in external DRAM memory, is 0.453 J [5]. Higher speeds have been achieved using more powerful devices (over 20 fps on a ZCU104 card), but this comes at the cost of higher power consumption of up to 8.8W on the device [6].

Conclusion

The GDED’s lines of research combine in-depth knowledge of information processing algorithms, the physical fundamentals of sensors, computer science and the design of complex digital systems. Research into the development of embedded systems for processing and interpreting hyperspectral images with applications in autonomous driving is one example of this group of researchers’ activities. Although functional prototypes capable of generating semantic segmentation images of complex scenes at video speeds using HSI sensors have already been verified and characterised, there is still some way to go in demonstrating that this technology could make a difference in future autonomous vehicle environment interpretation and guidance systems. The next challenges we will address in this line of research are manifold: modifying models and algorithms to improve the accuracy of object edge segmentation, optimising the data pre-processing phase to speed up computation, and bringing the processor closer to the sensor to obtain a more compact, faster and more efficient system for potential deployment on different mobile platforms.

[1] Motoki Yako, “Hyperspectral imaging: history and prospects,” Optical Review, Sep 2025.

[2] Michael West, John Grossman, and Chris Galvan, “Commercial snapshot spectral imaging: the art of the possible,”, MTR180488 internal report. The MITRE Corporation, 2019.

[3] Imad Ali Shah, Jiarong Li, Martin Glavin, Edward Jones, Enda Ward, and Brian Deegan, “Hyperspectral imaging-based perception in autonomous driving scenarios: Benchmarking baseline semantic segmentation models”, in 2024 14th Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing (WHISPERS), 2024, pp. 1–5.

[4] Koldo Basterretxea, Jon Gutiérrez-Zaballa, Javier Echanobe, and María Victoria Martínez, “HSI-Drive”, Zenodo Version v2.1.110.5281/zenodo.15687680

[5] Jon Gutiérrez-Zaballa, Koldo Basterretxea, and Javier Echanobe, “Optimization of DNN-based HSI Segmentation FPGA-based SoC for ADS: A Practical Approach”, ACM Journal of Sistems ARchitecture, 2025, doi 10.1145/3748722.

[6] Jon Gutiérrez-Zaballa, Koldo Basterretxea, Javier Echanobe, M. Victoria Martínez, Unai Martinez-Corral, Óscar Mata-Carballeira, Inés del Campo,”On-chip hyperspectral image segmentation with fully convolutional networks for scene understanding in autonomous driving”, ACM Journal of Systems Architecture, Vol. 139,2023,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sysarc.2023.102878.